Carbon fiber in commercial aviation has gotten complicated with all the marketing jargon and manufacturer claims flying around. As someone who’s followed composite aircraft development since the 787 program launched, I learned everything there is to know about how this material actually changed the game. Today, I will share it all with you.

That’s what makes the 787 Dreamliner’s story endearing to us aviation nerds — it wasn’t just a new airplane, it was a bet-the-company gamble on building planes from fundamentally different stuff.

Why Boeing Went All In on Carbon Fiber

Probably should have led with this section, honestly — the “why” matters more than the “what.”

Carbon fiber composites beat aluminum in ways that matter for airplanes. They’re roughly 50% lighter at equivalent strength. They don’t fatigue the way metals do. They don’t corrode. And you can mold them into shapes that would be flat-out impossible with sheet metal.

For airplanes where every pound burns fuel, those advantages add up fast.

What Carbon Fiber Composites Actually Are

I’m apparently in the camp that wants to understand materials at a fundamental level before talking applications. The basics are straightforward enough: thousands of hair-thin carbon strands get bundled together and locked in place with epoxy resin. The fibers give you strength and stiffness. The resin holds everything together and moves loads between fibers. Neither works alone — together they outperform both.

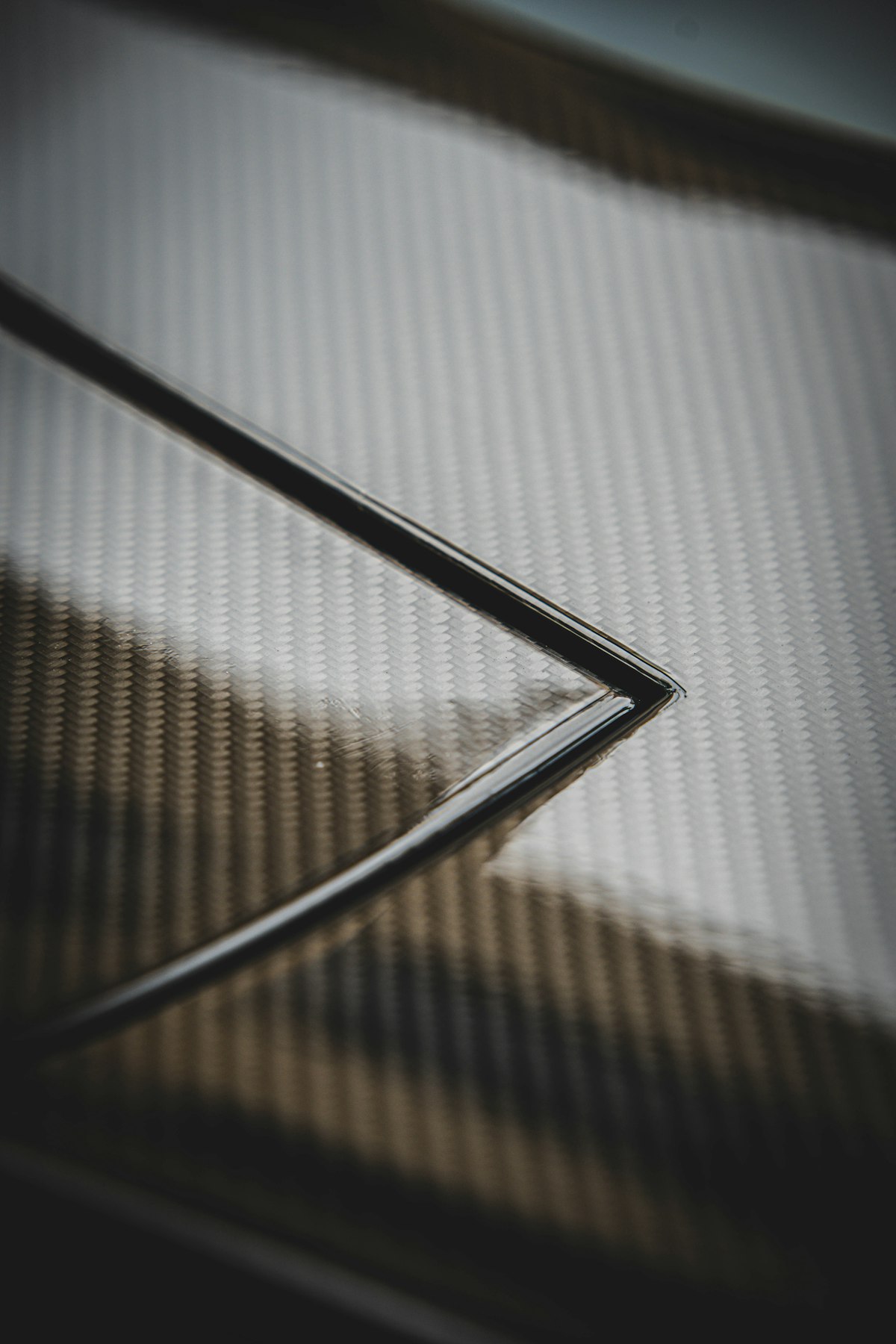

Here’s the clever part that took me a while to fully appreciate. Unlike aluminum, which behaves pretty much the same no matter which direction you push or pull it, composites are directional. Strongest along the fibers, weaker across them. So engineers stack layers at different angles — 0°, 45°, -45°, 90° — creating a material that handles loads from any direction. You’re basically designing the material and the structure at the same time. Metal can’t do that.

The 787: Where Composites Went Mainstream

When Boeing’s Dreamliner first flew in 2009, roughly 50% of its structural weight was carbon fiber composite. Compare that to about 10% on the older 777 and basically zero on the 767. Boeing used composites for the fuselage barrels, wing structures, tail assembly, doors, and floor beams.

The payoff showed up everywhere passengers could feel it:

- 20% better fuel burn compared to previous-generation jets

- Higher cabin humidity — composites don’t corrode, so Boeing could pump more moisture into the air without worrying about the structure rotting from inside

- Bigger windows — composite structures handle the cutouts better than aluminum skin

- Lower cabin pressure altitude — a stronger pressure vessel meant they could simulate a lower altitude inside, so you feel less awful after a long flight

Building Planes from Carbon Fiber

The manufacturing side is where things get genuinely difficult, and it’s where Boeing spent billions learning hard lessons.

For the fuselage, robots lay down narrow strips of carbon fiber tape — called automated fiber placement — building up barrel sections layer by layer. Wing components use resin transfer molding, where dry fiber preforms get infused with resin under pressure. Airbus pioneered some of this for the A350.

The typical sequence runs like this:

- Layup: Sheets of carbon fiber pre-impregnated with resin get placed in a mold with fiber angles carefully controlled

- Bagging: Vacuum bag goes over everything to squeeze out air and consolidate layers

- Curing: Into an autoclave — basically an enormous pressure cooker — to harden the resin

- Machining: Trim and drill the cured parts for final assembly

- Inspection: Ultrasonic and X-ray scanning catches internal flaws you’d never see from outside

Keeping Quality Under Control

This is the part that keeps composite engineers up at night. Metal defects tend to announce themselves — cracks you can see, dents that are obvious. Composite flaws can hide deep inside a part with zero surface indication. Every single component gets scanned ultrasonically, generating detailed maps of internal structure. Machine learning now helps analyze those maps, catching anomalies that human inspectors might miss on a long shift.

Sensors embedded directly in the molds track temperature, pressure, and cure progression in real time. Anything drifts outside spec and the system flags it before a bad part gets anywhere near the assembly line.

The Weight Savings Snowball

Here’s something I didn’t fully grasp until I dug into the engineering: lighter structure triggers a cascade. When the airframe weighs less, you need smaller engines to hit the same performance targets. Smaller engines burn less fuel. Less fuel means smaller tanks. Lighter airplane needs lighter landing gear. Lighter gear needs smaller brakes. Engineers call it the snowball effect — one pound saved in primary structure can yield 1.5 to 2 pounds of total aircraft weight reduction.

The Downsides Nobody Advertises

Carbon fiber isn’t all upside, and anybody telling you otherwise is selling something.

- Hidden damage: A ground vehicle bumps the fuselage and the surface looks fine. Internally? Could be delaminated. Requires specialized inspection to find out

- Repair headaches: You can’t just rivet a patch over composite damage. Repairs need specialized facilities and certified technicians

- Lightning strikes: Carbon fiber conducts electricity, but not as well as aluminum. Extra protection systems needed to handle strikes safely

- UV and moisture: Long-term environmental exposure has to be managed with protective coatings

Airlines had to completely rethink their maintenance programs for composite aircraft. Different training, different tools, different inspection intervals.

What Came After the 787

Once Boeing proved the concept worked at scale, everyone followed:

- Airbus A350: 53% composite by structural weight — slightly more than the 787 — with Airbus’s first composite fuselage

- Boeing 777X: Got the largest composite wings ever built, though Boeing stuck with aluminum for the fuselage (learned some lessons about manufacturing complexity)

- Airbus A220: Brought significant composite content down to the smaller narrowbody market

- Business jets: Bombardier, Gulfstream, and Dassault all went heavy on composites in their latest models

Where This Goes Next

The next generation of composite technology is already taking shape. Thermoplastic composites can be welded together and reshaped after curing — opening up manufacturing options that thermoset epoxies can’t match. Out-of-autoclave processes skip the expensive pressure cooker step entirely. Bio-based resins are starting to address the environmental footprint of petroleum-derived epoxies.

What started as a bold experiment with the 787 has become standard practice. The question for next-generation aircraft isn’t whether to use composites — it’s how much, and which new types. The planes your grandkids fly on will be built from materials we’re still figuring out today, but the revolution that started with carbon fiber and the Dreamliner isn’t slowing down.